The Guardian tells us that this week (May 10, 2019) the UN’s Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services warned that a million species face extinction thanks to human activity.

The Khushwant Singh Literary Festival (KSLF) believe it is a cliche worth repeating that we cannot underestimate the importance of ecology and climate change.This is in keeping with KS’s concerns for a green planet and his abiding interest in nature.

His description of the Monsoon, in what is perhaps his best known book, Train To Pakistan, is considered a masterpiece in literature. Comparable to some of the best in literature.

He has written on the Indian summer too, and quoted Kipling on the endless days of heat and dust. Nature’s festival of colors never ceased to amaze him.

KSLF, together with grow-trees have been planting trees for every speaker at the KSLF since inception at Kasauli in 2012. KSLF has also helped set up water harvesting systems in Kasauli, a region where water is scarce.

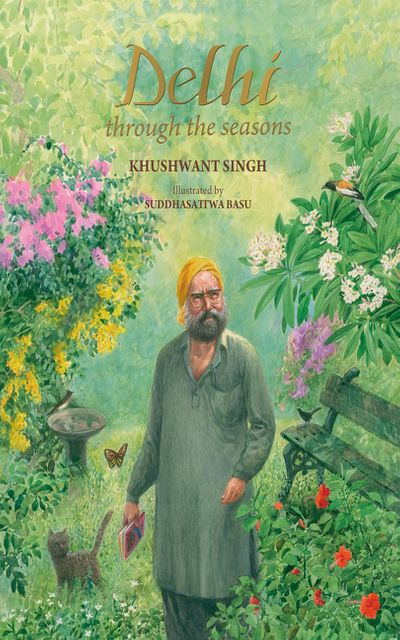

His books, Nature Watch and Delhi Through the Seasons, is the diary of a nature lover patterned after the traditional Baramasi of Indian poets. It tells you of trees, flowers, fruits, birds, snakes, insects and animals to be seen during the twelve months of the year in and around Delhi. It also tells of the many fairs and festivals celebrated in the country; how clouds are formed and what their shapes and movements mean; why hailstorms come in spring and early summer and not in winter; how birds communicate with each other and why their calls vary with the seasons. With the descriptions of nature are included poems on natural phenomenon by poets like Kalidasa, Guru Nanak, Meer Taqui Meer, Ghalib, Akbar Ilahabadi, Tagore, Rudyard Kipling and many others.

But few know of how It All Began. Here it is with the Britain connection in KS’s own words from his book, Trees of Delhi:

“MANY YEARS ago when I was a young man, I happened to spend a summer with my friends, the Wints, in Oxford. Guy Wint was on the staff of The Observer and was away in London most of the day. His wife, Freda, had converted to Buddhism and was also out most of the time meeting fellow Buddhists. Their son, Ben, was at a boarding school. For company I had the Wint’s three-year-old daughter, Allegra. In the mornings I worked in my room. When Allegra returned from her nursery school, I gave her a sandwich and a glass of milk before we went out for a walk. Since she knew the neighbourhood, she led the way along paths running through woods of oak, beech and rhododendron to the University cricket grounds. I would watch the game for a while—the Nawab of Pataudi often played there—buy her an ice-cream and then follow her back homewards. Allegra, or Leggie as we called her, was a great chatterbox as well as an avid collector of wild flowers. Our return journey always took much longer as I had to pick whatever flower she wanted. She would point in some direction and order: ‘I want those snow-drops behind that bush.’ Or shout, ‘Goody! I want them blue-bells! I want lots of them for Mummy!’Then there were periwinkles and lilies-of-the-valley, and many others. By the time we had our hands full of flowers, Leggie was too tired to leg it home. I had to go down on my knees for her to climb up on my shoulders. She had her legs round my neck and her chin resting on my head. A game she enjoyed was to stick flowers in my turban and beard. By the time we got home, I looked like a wild man of the woods. It was from little Allegra Wint that I learnt the names of many English wild flowers. On weekends when the Wint family was at home we spent most of the day sunning ourselves in the garden. Since the Wints had a few cherry and apple trees, there were lots of birds in their garden. The dawn chorus was opened by thrushes and blackbirds. They sang through the day till late into the twilight. Both birds sounded exactly alike to me. Freda would quote Robert Browning to explain the difference: That’s the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over, Lest you should think he never could recapture The first fine careless rapture. The wise thrushes of Oxford had not read Browning and rarely repeated their notes. Or perhaps the blackbirds deliberately went over theirs again to confuse people like me. Then there were chaffinches, buntings, white throats, and many other varieties of birds whose songs became familiar to me. That summer, I heard nightingales on the Italian lakes and in the forest of Fontainebleau.(Contrary to the popular notion, nightingales sing at all hours of the day and night). Back home in Delhi I felt as if I was on alien territory as far as the fauna and the flora were concerned. Before I had gone abroad, I had taken no interest in nature. When I returned I felt acutely conscious of this lacuna in my information as I could not identify more than a couple of dozen birds or trees. Getting to know about them was tedious but immensely rewarding. I acquired books on trees, birds and insects and spent my spare time identifying those I did not know. I sought the company of bird-watchers and horticulturists. Gradually my fund of information increased and I dared to give talks on Delhi’s natural phenomena on All India Radio and Doordarshan. For the last many years I have maintained a record of the natural phenomena I encounter every day. However, my nature-watching is done in a very restricted landscape, most of it in my private back garden. It is a small rectangular plot of green enclosed on two adjacent sides by a barbed wire fence covered over by bougainvillaea creepers of different hues. The other two sides are formed by my neighbour’s and my own apartments. He has fenced himself off by a wall of hibiscus; I have four ten-year-old avocado trees (perhaps the only ones in Delhi) which between them yield no more than a dozen pears every monsoon season; and a tall eucalyptus smothered by a purple bougainvillaea. There is a small patch of grass with some limes, oranges, grape-fruits and a pomegranate. I do not grow many flowers; a bush of gardenia, a couple of jasmines and a queen of the night (raat-ki-rani). Since my wife has strictly utilitarian views on gardening, most of what we have is reserved for growing vegetables. At the further end of this little garden I have placed a bird-bath which is shared by sparrows, crows, mynahs, kites, pigeons, babblers and a dozen stray cats which have made my home theirs. Facing my apartment on the front side is a squarish lawn shared by other residents of Sujan Singh Park. It has several large trees of the ficus family, a young choryzzia and an old mulberry. I have a view of this lawn from my sitting-room windows framed by a madhumalati creeper and a hedge of hibiscus. What perhaps accounts for the profusion of bird life in our locality are several nurseries in the vicinity, the foliage of many old papari (Pongamia glabra) trees and bushes of cannabis sativa (bhang) which grow wild. I have not kept a count of the variety of birds that frequent my garden but there is never a time when there are none. Also, there are lots of butterflies, beetles, wasps, ants, bees and bugs of different kinds. There was a time when I spent Sunday mornings in winter in the countryside armed with a pair of binoculars and Salim Ali’s or Whistler’s books on Indian birds. My favourite haunts were the banks of the Jamuna behind Tilpat village; Surajkund, the dam which supplies water to its pool; and the ruins of Tughlaqabad Fort with its troops of rhesus monkeys. I still manage to visit these places at least once a year to renew acquaintance with water fowl, skylarks, weaver birds and variety of wild plants like akk, debla, vasicka, mesquite, Mexican poppy and lantana which grow in profusion all round Delhi.”